Novgorodian Icon-Painting (part3)

I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII

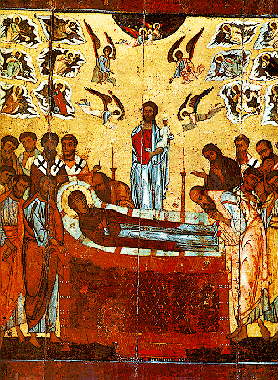

The Dormition from the Church of the Nativity of the Virgin in the Desyatinnyy Monastery is an example of the Byzantine influence in easel-painting. This beautiful icon, with its thick, opaque colouring, though somewhat rigid composition, is distinguished by the complex iconographic conception. It portrays the traditional Twelve Apostles gathered round the Virgin on her couch, the Fathers of the Church, and Christ, who stands in the centre holding in his arms a swaddled child symbolizing the Mother Mary's soul. In the upper section we see the Apostles borne aloft on clouds, a group of angels, and the Archangel Michael soaring towards heaven with the Virgin's soul. The sensitive faces of the Apostles, especially in the right-hand part of the composition, bespeak the artist's thorough knowledge of Byzantine works of the Comnenian period. The cast of the features in the left-hand group is not so obviously Greek. They are softer, more intimate. Particularly expressive is the head of the Apostle bending over the Virgin's body and peering intently into her face as if saying the last farewell.

The Dormition, Early XIII century.

Parallel to the Byzantine inlluence in the twelfth century, another trend arose iin which the local features of Novgorod prevailed over the Byzantinge features that were introduced. This second trend, more original and democratic, was associated with the strengthening of the Veche system which had led to the curtailment of the power of the Prince. The merchants and the craftsmen, who were beginning to play an increasingly bigger role in the life of "Gospodin Velikiy Novgorod", became more and more conscious of their power. And their tastes were naturally bound to make themselves felt in art. It was in this way that another tendency gradually began to grow and spread in the art of Novgorod. It did not supersede the first but existed alongside with it. And in the end it won.

A typical example of this new and more original Novgorodian style of the twelfth century is to be seen in the icon of the Virgin of the Sign whose intercessionary powers, according to the legend, were invoked in the defence of Novgorod when the city was besieged by the Suzdalians in 1169. The reverse side of the icon (the obverse has been lost) contains a rather unusual composition: the Apostle Peter and Saint Natal'ya address a prayer to Christ. The figures are short, with large heads. The manner of painting is free and natural, reminiscent of the fresco technique. The face of St. Peter, with vigorous, dramatic highlights, indicates a softening of Byzantine austerity and the emergence of a new, psychological element, more emotional and intimate.

St. Nicolas, Middle of XIII century.

Passing on to the thirteenth century, we must at once stress that for Novgorod, too, it was a "dark century". Though the Tartars never actually occupied the city, their invasion had affected the north of the country. Construction of stone churches was almost discontinued, as fear of the Mongol hordes had made people more cautious and circumspect. Cultural relations with south Russia and Constantinople were discontinued. This isolation of Novgorod, which retained its independence, spurred the development of local artistic movements fed by the springs of folk art. This is not to say that the Byzantine tradition had been completely forgotten. It existed as a heritage of the twelfth century, and if it did not determine the ways of the development of Novgorodian art it retained its importance for individual masters, as evidenced by the icon of St. Nicholas.

The painter of this icon, which came from the Dukhov Monastery and which was painted closer to the middle of the thirteenth century, was familiar with the art of the preceding century. The face of the saint retains much of the Byzantine austerity and grimness. But there are also many new features in the treatment of the face, which were later to be developed: notably a greater stress on line and on ornamentation (especially in the rendering of the folds of skin and locks of hair). The lines look as if they were cut into the panel, as in etchings. The Byzantine master would never have rendered form so graphically. The colouring, too, with its contrasts of pale and vivid tints, is distinctly unByzantine. The partially cut off figures of saints at the margins (one can identify St. Symeon Stylites and Sts. Boris and Gleb) and the half - length figures in the upper part of the icon (Archangels Michael and Gabriel) and in the medallions (Athanasius, Anisim, Paul and Catherine) are painted in a much freer way and have a much gentler expression than St. Nicholas.