Novgorodian Icon-Painting (part 11)

I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII

The last quarter of the fifteenth century can be regarded as the starting point of this process which reached its culmination in the middle of the sixteenth century.

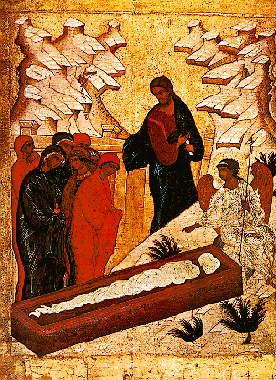

At that time, too, Novgorodian artists continued to produce large numbers of iconostases. One of them, from the Church of St. Nicholas at the former Gostinopolsky Monastery, can be dated with considerable accuracy 1475 or near 1475 on the strength of an inscription on the church bell. The iconostasis consisted of a half - length Deesis tier, a feast - day tier and a half - length Prophets tier. The icons which have survived from this ensemble are distinguished by a certain sleekness which replaced the former richness of painting. But there is the same vividness and intensity of colour and the keen sense of silhouette (especially in the figure of the Archangel Michael and in the Holy Women at the Sepulchre). In this latter scene, the diagonal position of the sepulchre makes the scene more three - dimensional than it is on the icons of the first half of the fifteenth century. This effect is heightened by the figure of Christ which stands in front of the wall but behind the rock on the right, while the angel seated at the head of the sepulchre is shown in front of the rock. The Holy Women are placed in the zone between the angel and Christ. All this lends a certain depth to the composition. But the strongly stylised rocks in the background, which effectively frame the figure of Christ, come to the artist's assistance, as it were, and keep the composition on the two - dimensional plane of the panel.

The Holy Women at the sepulchre, Near 1475 y.

The Tretyakov Gallery has a splendid icon with half - length figures of the Prophets Daniel, David and Solomon, which at one time must have formed part of a church iconostasis. The flowing parabolas of its neat, svelte figures, with their streaming hair, crowns and headbands are extremely beautiful. Their mantles, held together by clasps, the shoulder pieces of tunics decorated with precious stones, the edges of cloaks studded with pearls - all give a great brilliance to the icon, which is heightened by the glow of wonderfully pure and vivid colours. In the treatment of the faces and hands one can already feel the desiccated standardized manner of execution that was to become especially typical of sixteenth - century icons.

The Prophets Daniel, David and Solomon, Last quater of XV century.

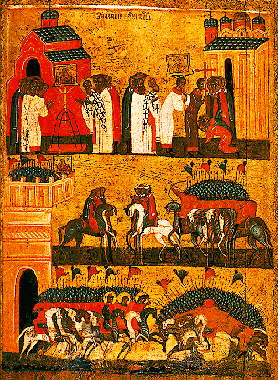

A comparison of the Tretyakov Gallery's Battle between the Novgorodians and the Suzdalians with a similar icon from the Russian Museum offers a clear indication of the direction in which the style of Novgorodian icon - painting was changing at the end of the fifteenth century. All forms in it have acquired a certain miniature character and there has appeared a fragility unusual in earlier work (especially indicative in this respect is the representation of horses - solid and rather squat in the Novgorodian icon and particularly trim and elegant in the Muscovite). The narrative itself loses much of the graphic clarity that was so impressive in the Novgorod Museum icon. In the upper band for example, the two converging movements neutralize each other, and the isolated church of the Saviour and the numerous buildings of the Kremlin are no longer in opposition. The top of the fortress wall, with the Novgorodians hiding behind, has lost its architectonic quality: it seems to hang in the air with no firm support' beneath, and it therefore remains unclear where the ambassadors come from. Finally, the lower gates are shown frontally with the result that the warriors near them seem to be passing by the gate and not emerging from it as in the Novgorod icon. No attempt is made to exploit the spatial intervals which were so expressive in the Novgorodian work. As a result, the Tretyakov Gallery icon lacks clarity of composition, but has instead a facility of execution that bespeaks the calligraphic propensities of the artist who prizes above all the elegance of line which he handles with superlative skill.

Battle Between the Novgorodians and the Suzdalians, Late XV century.

Sts. Florus and Laurus, Late XV century

The icon of Sts. Florus and Laurus is another masterpiece of Novgorodian icon painting of the late fifteenth century. In this work, a traditional subject acquires a truly classical form. A difficult compositional problem is solved with amazing skill through the principle of symmetry. The figure of the Archangel Michael, flanked by Sts. Florus and Laurus, is not right on the central axis but is shifted somewhat to the right. To compensate for this disturbance of the centricity, the artist adds two shrubs on the left which restore the required balance of the component parts. The Archangel holds the bridles of two horses, a white and a black, which, with their sharp - edged silhouettes, recall a heraldic pattern. On the same axis with the Archangel are three grooms. They form a free - standing group which does not upset the centricity of the composition. The grooms hold whips with which they drive the horses standing in the water. The scene of watering is treated in such a way that it, too, is subordinated to the overall centricity of composition. The horses face different ways, and though there are five horses in the right - hand group and only four in the left-hand, the artist achieves an ideal balance. What is more, there is nothing contrived, pedantic, mathematically exact about this balance. For all its symmetry, the composition in general looks flexible and elastic owing to the free distribution of figures about the plane of the panel. Compared with the icons of the first half of the fifteenth century, the tints are less intense, and the hues are paler but so harmonious that the colour scheme is extremely refined.

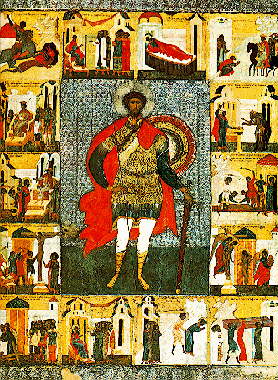

St. Theodore Stratelates, End of XV century.

The hagiographical icon of St. Theodore Stratelates from the Novgorod church of the same name (now in the Novgorod Museum) dates from the end of the fifteenth century. The icon is extremely beautiful in colour and contains a number of stylistic features heralding the approach of the sixteenth century: the saint cuts an elegant, dashing figure, the architectural backgrounds in the scenes have become more complicated, the figures are shown in greater movement, and the compositions now include more spatial areas, which makes it more three - dimensional. But such esteemed properties of Novgorodian panel - painting as the delicate sense of silhouette and the glow of bright, pure colours has not yet been lost. The famed bi - partite tablets from St. Sophia, now in the Novgorod Museum, marked the swan - song of Novgorodian icon - painting in the fifteenth century. These small icons, painted on well - primed canvas, belong to different masters who worked at the end of the fifteenth century and later. Together they provide a clear picture of the creative quests of Novgorodian icon - painters of the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. They are also significant as a monument of outstanding iconographic importance, for there is no other set of icons comparable for wealth of subjects.